The primary question of this chapter is how social, cultural, and economic forces impact the ways that the cultural value of books is constructed. In particular, this chapter examines how the value of books is constructed through paratext. Through a close reading of its paratext, this chapter will suggest that Yann Martel’s Life of Pi shows how a sense of literary value is produced.

Paratext is all of the information that surrounds a story and that create expectations about the story. Thus, it is involved in the continuous process of creating literary value. Paratext can include:

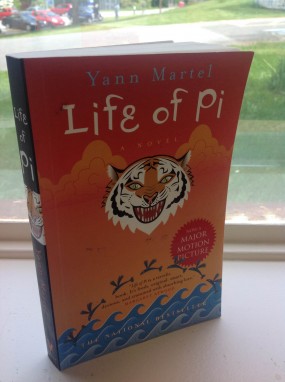

Back cover and spine of the 2011 Vintage Canada edition of Life of Pi by Yann Martel. Photo by Alissa McArthur / Canadian Literature, 2014. Used with permission from Random House of Canada.

- The title of the text;

- The book’s cover;

- The front matter of the text;

- The dedication of a text;

- The forward to the text;

- What is written on the book jacket;

- And the footnotes and endnotes of the text.

Even things like font and pagination can dramatically change the look and feel of a book. Some authors have a great deal of input into the look and feel of a book, but the publisher, in consultation with the writer, often has the final say about matters of paratext. In a crowded literary marketplace where books compete for space, publishers seek to designs books so they stand out on bookstore shelves.

Paratext can change the way that a text is read, understood, and consumed. Perhaps the most important work on paratext is by French literary theorist Gérard Genette, who argues that texts are

rarely presented in an unadorned state, unreinforced and unaccompanied by a certain number of verbal or other productions, such as an author’s name, a title, a preface, illustrations. And although we do not always know whether these productions are to be regarded as belonging to the text, in any case they surround it and extend it, precisely in order to present it, in the usual sense of this verb but also in the strongest sense: to make present, to ensure the text’s presence in the world, its “reception” and consumption in the form … of a book. (1)

Genette offers the example of James Joyce’s Ulysses, a text that many literary critics find valuable, asking, “limited to the text alone and without a guiding set of directions, how would we read Joyce’s Ulysses if it were not entitled Ulysses?” (2). The title of a work of literature is not merely descriptive. A good title creates a set of readerly expectations about a text. Joyce’s title Ulysses, for example, alludes to the famous hero known in Greek as Odysseus and his journey homeward recounted in Homer’s Odyssey. Martel’s title doesn’t help the reader but forces her to ask the question: Who is Pi?

Paratext and Life of Pi

Cover of the 2011 Vintage Canada edition of Life of Pi by Yann Martel. Photo by Alissa McArthur / Canadian Literature, 2014. Used with permission from Random House of Canada.

For literary critic Barbara Herrnstein Smith, “texts, like all the other objects we engage with, bear the marks and signs of their prior valuing and evaluation by our fellow creatures and are thus, we might say, always to some extent pre-evaluated for us” (183). To see what Smith is getting at here, consider the role of paratext in the process of creating literary value in Martel’s Life of Pi. For example, the 2011 Vintage Canada edition carries several markers signifying value to the potential reader. For one, the cover proclaims Life of Pi is “the national bestseller,” suggesting that many other readers have already valued the book. As well, a large red badge announces the book is “now a major motion picture,” which indicates a multi-million dollar investment. Moreover, stating the book was the national bestseller and not simply a bestseller implies that, at some point, Life of Pi was the number-one-selling text in Canada. Many readers have paid to read this book, selecting it over other works of Canadian fiction, and this claim to being the bestseller helps to establish the book as a desirable thing to own.

According to Smith, evaluators make both tacit and explicit assumptions when praising literature (183). For the paratextual materials to succeed in constructing the value of Martel’s work, the reader must decode a collection of these assumptions about how literature comes to be valuable. The book cover blends the economic value of the text with its artistic merit by including a blurb from author Margaret Atwood: “Life of Pi is a terrific book. It’s fresh, original, smart, devious, and crammed with absorbing lore.” Atwood’s endorsement is valuable in its own right because of her status as a recognized literary celebrity in Canada. The recommendation from Atwood is a suggestion to readers who like her novels that they will also find Lie of Pi engaging. When Atwood says that Martel’s work is “fresh, original, [and] smart,” she draws an implicit contrast with other works of literature that might be considered stale, derivative, and dumb.

The back cover further reinforces the literary merit of the book, as the reader is told that Life of Pi won the Hugh MacLennan Prize for Fiction, and that it was a finalist for the both Governor General’s Award for Fiction and the Commonwealth Writer’s Prize for Best Book. The paratext of Life of Pi constructs its literary value by showing how consumers, other authors, and awards committees have already found the text valuable. The paratext also suggests an international and national importance. The juxtaposition of these two announcements establishes that the novel is at once an important work of Commonwealth writing and an important work of Canadian writing. Because the novel deals with cultural hybridity (Canada and India), this dual marking of value seems deliberate.

Blurbs from inside the 2011 Vintage Canada edition of Life of Pi by Yann Martel. Photo by Alissa McArthur / Canadian Literature. Used with permission from Random House of Canada.

None of this can prove that Life of Pi is a great work of literature. Indeed, this chapter is purposefully ambivalent on this question because no measurement of literary quality outside the systems of human evaluation exists. We describe several of these systems in this guide. But we can see how Life of Pi and other contemporary works of Canadian literature use paratext as a means of fashioning and marketing the text as a valuable object for readers to acquire.

Questions to Consider

- Consider the shelf displays in bookstores. What do you notice about the way books are displayed? Which books face out so the cover faces shoppers and which are arranged so only the spine shows? Do you notice patterns in book design among different genres, such as graphic novels, poetry, or non-fiction?

- What role do award stickers play in communicating literary value?

- How might the reader’s engagement with Life of Pi change if the text did not announce itself as valuable through the use of award badges and blurbs?

- Write a blurb for your favourite book. Remember that most book blurbs are short one-sentence expressions of praise. What aspect(s) of the book would you highlight in the blurb?

Works Cited

- Genette, Gérard. Paratexts: Thresholds of Interpretation. Trans. Jane E. Lewin. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1997. Print.

- Martel, Yann. Life of Pi. 2001. Toronto: Vintage Canada, 2011. Print.

- Smith, Barbara Herrnstein.

Value/Evaluation.

Critical Terms for Literary Study. Ed. Frank Lentricchia and Thomas McLaughlin. Chicago: U of Chicago P, 2010. 177–85. Print. - Bourdieu, Pierre. The Field of Cultural Production: Essays on Art and Literature. Trans. Randal Johnson. New York: Columbia UP, 1993. Print.

©

©